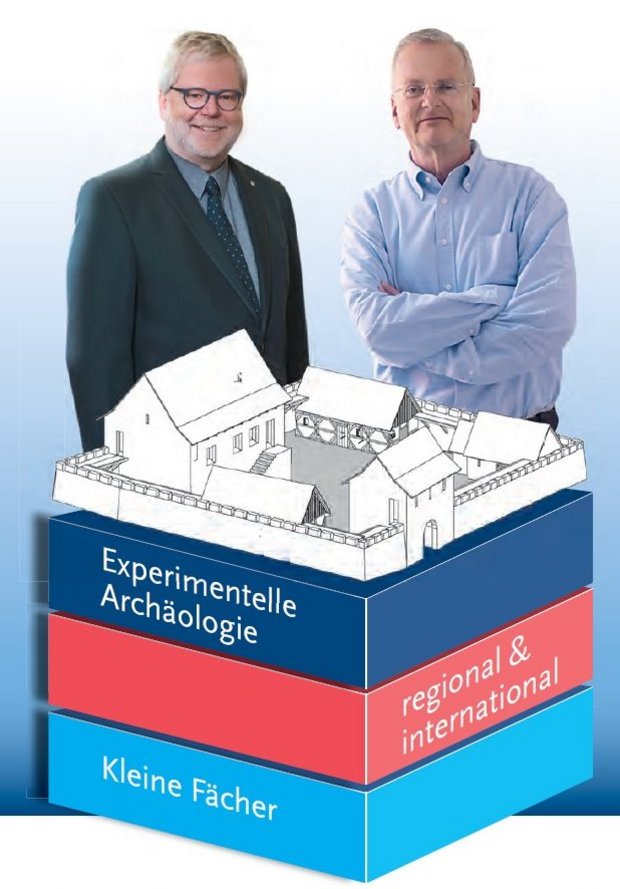

Stepping into the past always opens up paths: knowing the past better opens up a fuller understanding of the present and enables planning for the future. Bamberg researchers in archaeology, heritage conservation studies, Oriental studies, European ethnology and art history work together collegially in a unique interdisciplinary network.

They explore, document and preserve a wealth of humanity’s tangible and intangible cultural assets. There is much to do the UNESCO World Heritage city of Bamberg itself, but Bamberg scholars also often pack up their cameras, scanners, UV lamps and sketchpads and work all over the world.

Short lines of communication

“Could you just take a quick look at this?”

These words often stand at the beginning of stories of great things. Uttered in the corridors of the Institute for Archaeology, Heritage Conservation Studies and Art History (IADK), they frequently spark an enthusiastic response. “We rented a car once and went to France for five days. We came back with two projects and an outline plan for a new degree programme.” Professor Stephan Albrecht, who holds the Chair in Medieval Art History in Bamberg, values the easy, direct communication with fellow researchers that is possible at the University of Bamberg.

“Could you just take a look at this?”,

Albrecht asked his colleague Thomas Eißing, the Director of the Laboratory for Dendrochronology – and Eißing promptly joined him on a trip to Paderborn to take a closer look at wooden Gothic sculptures there.

The sculptures were surveyed and dated, a doctoral thesis was written, and the conceptualisation of a major exhibition of Gothic art was altered as a result.

“Might we just take a look?”,

Albrecht asked Elisabeth Taburet-Delahaye, director of the Musée de Cluny in Paris – and received permission to examine a famous statue of Adam with equipment including UV lamps and X-ray machines together with his colleague Rainer Drewello, professor of Materials and Preservation Science.

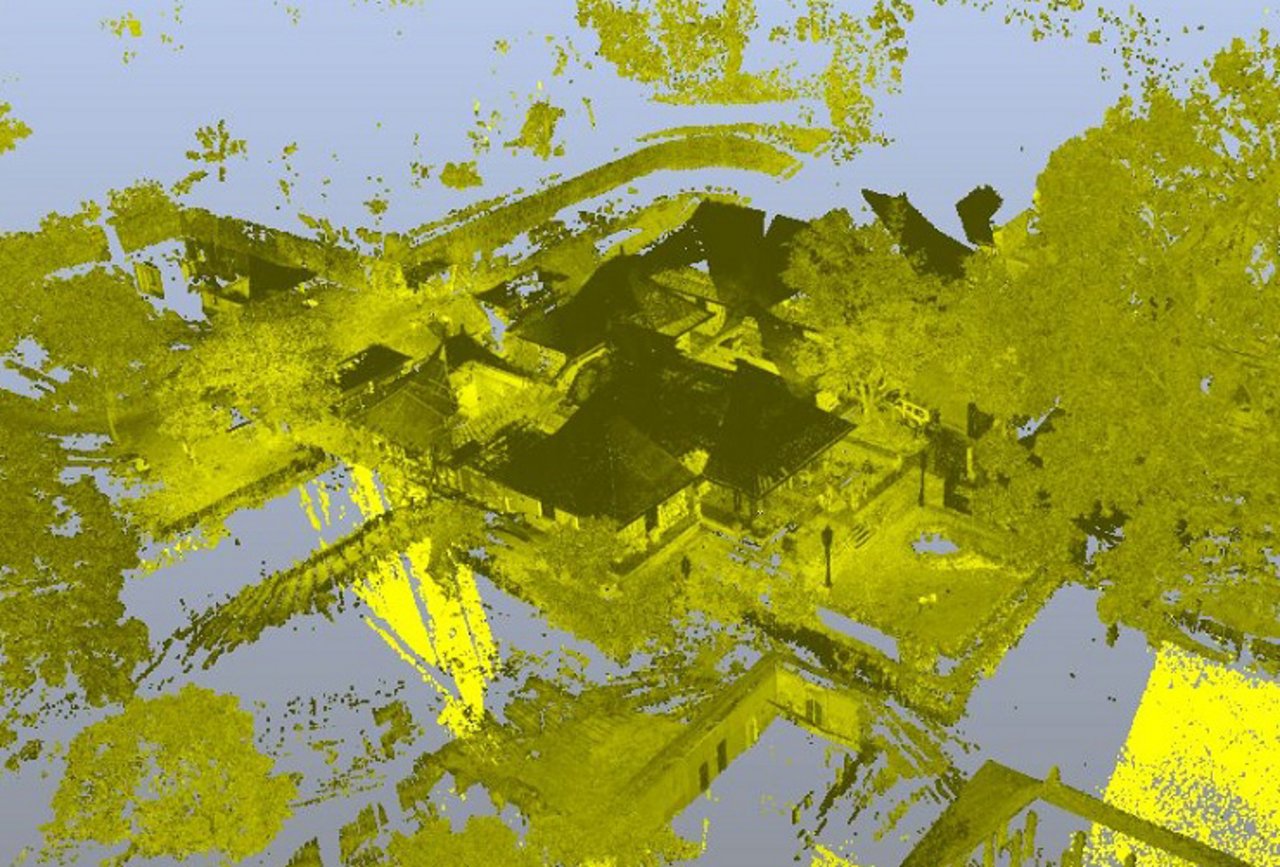

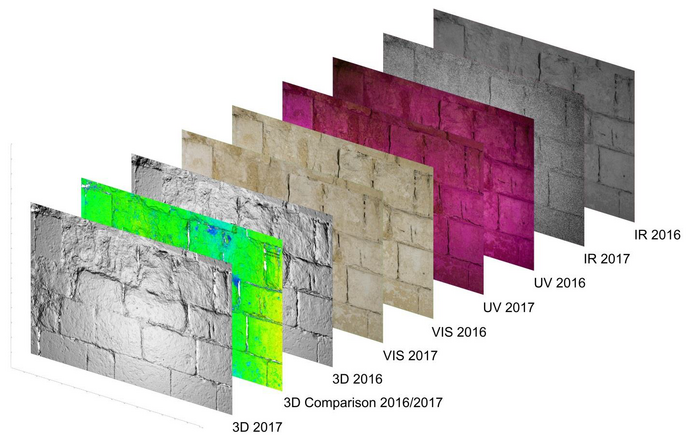

The statue is untypical, as Adam is not depicted with the apple that is usually included as an allusion to the fall of man. But the Bamberg researchers discovered that the statue does indeed refer to Adam’s expulsion from paradise: in the relevant passage from the Bible, an angel appears to Adam to announce his expulsion as Adam listens, and in this statue, Adam’s arm position can be interpreted as a gesture indicating that Adam is receiving a message. An examination of the statue with UV light revealed that it had previously been completely disassembled and reassembled (see the “Before/After graphic). By using 3D scanning, the Bamberg research team was also able to identify the niche in Notre Dame Cathedral where the statue must originally have stood.

Working directly with cultural treasures is a central focus. Questions are formulated from the perspective of the humanities and then investigated using methods from both the humanities and the natural sciences. “Some ideas lead only to dead ends”, Albrecht says, “but often we are indeed on to something and have a new discovery or a new narrative about an object or a process to show for it in the end. These quests motivate us, and that never stops.” What typically happens in Bamberg, then, is that several professors from different disciplines end up standing on scaffolding together and rounding off one another’s expertise perfectly.

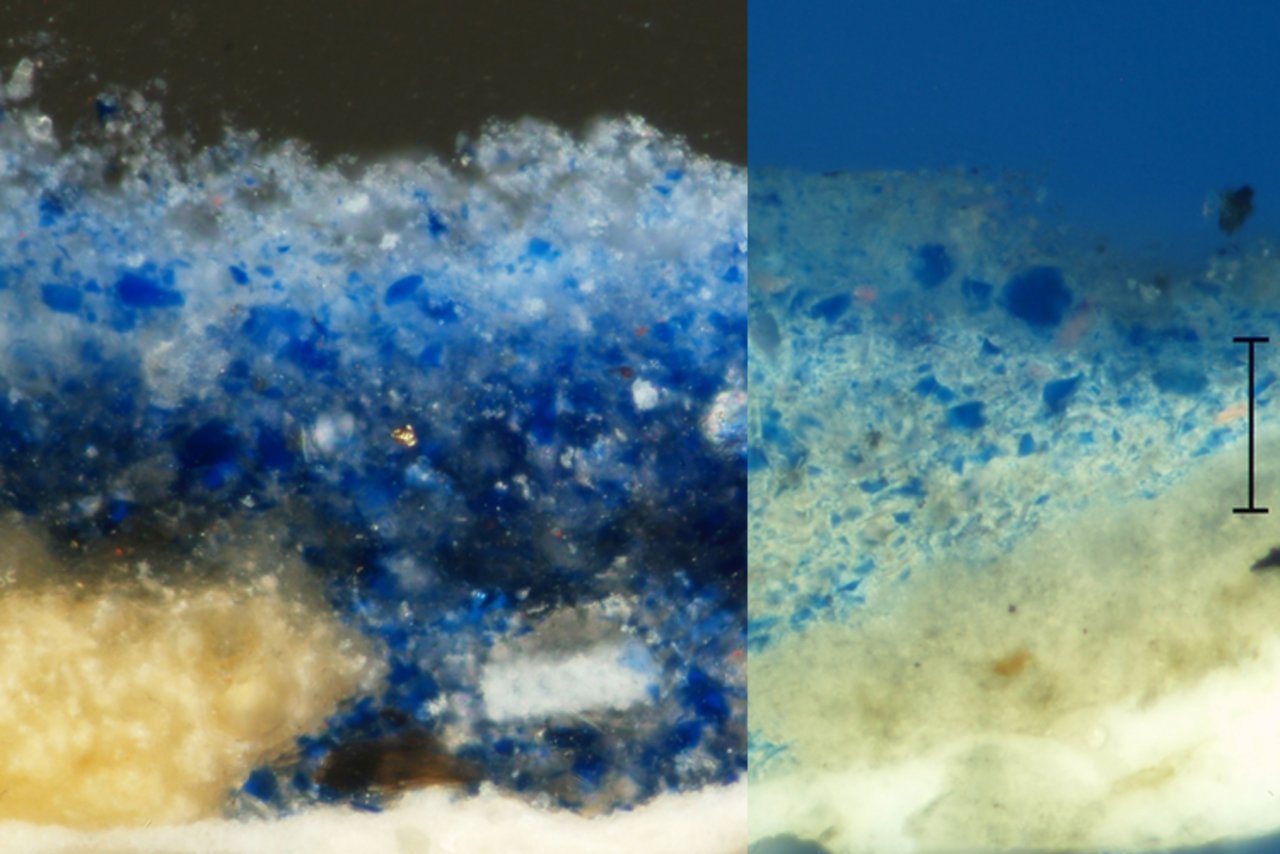

The project Medieval Portals as Places of Transformation can serve as a paradigmatic illustration of this. Six prominent portals in churches in Germany, France and Austria were examined. In Bamberg, the project looked at the magnificent Portal of Mercy at Bamberg Cathedral. The results are promising; heritage conservation expert Rainer Drewello is now able to describe the original colours and decoration of the portal much more precisely and to say how it has been altered over time. “To begin with, my question was: What is original about the portal? And what do we see today that has nothing at all to do with how it used to look originally?”

The same research project helped Stefan Breitling, an architect and professor of Building Archaeology, to gain a fuller understanding of how a building site was organised around 1200 CE. He was even able to trace what mistakes were made, for example during the erection of scaffolding, and thus how some cracks in the cathedral’s fabric arose that cause some concern today. “They built very quickly, they had good preliminary plans and pattern books – responsibilities for the work were distributed to a much greater extent than has previously been assumed, and it was a collective endeavour.” The art historian Stephan Albrecht can confirm this appraisal from the perspective of his own discipline, since it appears that the sculptures of figures on the portal were created in series. They were not the work of a single master, and this lends weight to the idea that long-held conceptions about artistic genius and single master builders with sole responsibility need to be revised. Some of the portal's sculptures were even installed in an unfinished state when money ran out in the middle of one specific work phase.

The boundaries of disciplines become blurred during the research process: an art historian may need to think like a chemist, an architect like a philosopher or a heritage conservation specialist like a historian. Combining interdisciplinary expertise from the humanities, engineering and materials sciences results in research achievements that far surpass what the individual disciplines could achieve alone. Working in such a network makes tackling major international projects possible and enables the biographies of buildings to be seen in a holistic fashion.

Intangible Cultural Heritage

But how can something constantly in flux be preserved: lives being lived, activities, customs, and rituals? The glass cabinets outside Heidrun Alzheimer’s office show current research projects at the Chair of European Ethnology. They examine both tangible and intangible cultural assets: everyday culture, fashion, the socio-cultural transformation of the Nuremberg district of Gostenhof from a rough neighbourhood to a trendy residential area with rising rents, the culture of Christmas mangers in a European comparison. Some projects deal with visible and tangible heritage and others with fluid phenomena.

In Alzheimer’s role as an expert on intangible cultural heritage, she often immerses herself in new forms of cultural expression. Traditions passed on orally such as popular songs, fairy tales and legends, traditional craft techniques such as lace-making, basket weaving, button-making, and resist block printing in combination with indigo blue dying, performing arts such as flamenco or choral singing, festivals and customs from “A” for Ansingen (“singing in”) to “Z” for Zoiglkultur (the culture of brewing Zoigl beer in communal breweries) and, finally, traditional knowledge about nature and the universe passed down through the ages on topics like Alpine farming, medicinal herbs, or traditional midwifery.

Heidrun Alzheimer places particular emphasis on one aspect of these traditions: protecting and preserving traditions does not mean conserving them in their current state but allowing them to continue to evolve and change; this is often misunderstood. Being included on cultural heritage lists focuses attention on communities and is not infrequently accompanied by a strong uptick in interest from tourists and the media which can facilitate the preservation of cultural practices but can also lead to a loss of authenticity and, especially in small communities, create excessive pressures on local inhabitants.

This multimedia feature presents the University of Bamberg’s Analysis and Preservation of Cultural Heritage research focus area.

Editing: Samira Rosenbaum

Writing: Dr. Martin Beyer

Video: Christian Beyer

Translation: Sarah Swift

Has your curiosity been piqued? You may wish to check out our multimedia features on other Bamberg research focus areas!