Anyone brave enough to embark on a research trip into medieval times is sure to encounter mind-boggling diversity. Even just the spans of time involved are vast: the Middle Ages run roughly from 500 CE to 1500 CE and thus span some one thousand years of European history.

Politics, religion, culture and languages: researchers in Bamberg have been exploring all of these and more for over 20 years now in a dedicated research centre. Historical studies, heritage sciences, linguistics and literary studies in various languages, Oriental studies, archaeology, theology and also philosophy join forces here to forge new paths into the Middle Ages.

“Essentially, two diametrically opposed perspectives exist: the medieval period is either perceived as ‘dark’ or as ‘romantic’”, English Studies scholar Professor Christoph Houswitschka († 2022) comments. “Popular takes continue to stress these facets as stubbornly as modern scholarship has shown them to be baseless.” And philologist Professor Ingrid Bennewitz adds: “We medievalists see ourselves not only as experts on the Middle Ages, but also and equally as specialists for the influence of this period on our own times.” Why does the medieval period still evoke so much fascination today? And how is it portrayed in modern media?

Diverse Research

How did people actually live in medieval times? What did they believe in? How did they talk? These are questions Bamberg researchers seek to answer. The 80 members of ZEMAS, the Centre for Medieval Studies, are connected by a shared fascination with this period. The centre brings together an enormously diverse range of disciplines – from such mainstream disciplines as German language, literature and culture and history to smaller niche disciplines like Jewish studies and heritage conservation – and enjoys international recognition. Disciplines with roots in the natural sciences contribute expertise that complements the perspectives of the humanities disciplines in exchanges and facilitates more comprehensive approaches to research questions.

“What makes ZEMAS special is that we look at research topics from multiple angles,” explains Ingrid Bennewitz, the Executive Director of ZEMAS. “There is a concentration in Bamberg of all the laboratories, instruments and scholarly disciplines needed for medievalism research.”

These different perspectives complement one another perfectly. A recent joint project on Richard the Lionheart highlights their fertile collaboration. An edited volume shedding light on the famous twelfth-century king from the vantage points of history, literary studies and theology has been produced by six Bamberg scholars and four additional German scholars.

European Identity

The more deeply researchers probe the historical medieval period, the better they understand how this age has shaped the present – both in obvious ways and in ways so subtle as to be barely perceptible. Medieval politics, the medieval legal order and medieval philosophy have exerted influence on the identity of modern Europeans. In relation to marriage and partnership, historians Professor Klaus van Eickels and Professor Christof Rolker see parallels between then and now.

The Medieval Period in Franconia

Franconia is a region with a particular draw for medievalists thanks to the wealth of research topics it is able to offer them. Archaeologists unearth rich medieval finds here, for example. Heritage Conservation experts draw on an array of different technologies to document buildings and architectural and ground monuments.

Time and again, researchers successfully coax the region of Franconia into yielding up new secrets:

The Ebstorf Mappa Mundi

The world as a system

Researchers in Bamberg are also interested in examining how Franconia was seen from the outside. The Ebstorf mappa mundi, a fourteenth-century world map from the Lüneburg Heath area featuring Bamberg, is a case in point. Historical geographer Professor Andreas Dix has studied this map and describes it as “not a geographical map, but a cosmology. This is an attempt to explain the world as a holistic system.” The map was most likely produced as an altarpiece for use on special ecclesiastical feast days.

Like a metro plan

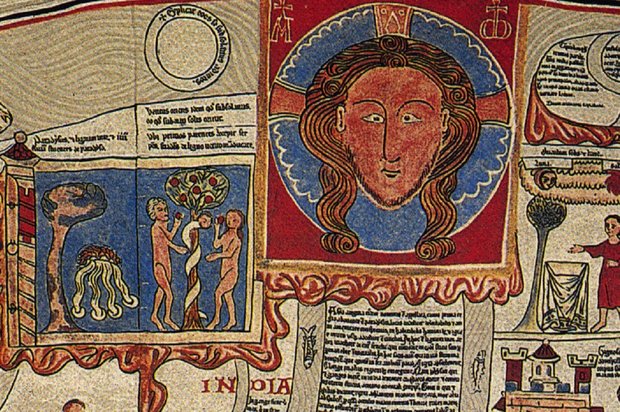

Andreas Dix compares the map with a public transport plan. The Ebstorf map shows the three continents of Asia, Africa and Europe connected by rivers and seas – at that time the main means of transportation. The map interprets the world from a fundamentally Christian stance. As geographer Andreas Dix explains, “Jesus Christ holds everything together, and the hands and feet drawn on the map show that beautifully. At the centre of the map, Jerusalem is shown, the city where Christ was crucified and resurrected.”

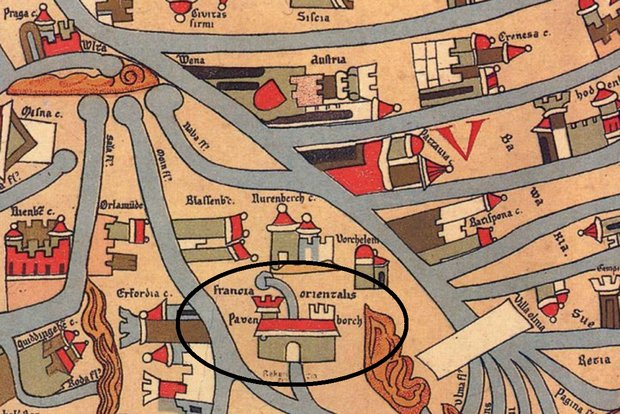

Franconian cities charted

At the bottom left of the map, Franconian cities including Bamberg (“Pavenborch”) and Nuremberg (“Nurenberch”) are depicted. Andreas Dix considers that these cities were probably known to the inhabitants of Ebstorf via trade relations. “A house on a bridge over the river Regnitz is used to depict Bamberg on the map – perhaps an early reference to the bridge town hall.” With a diameter of 3.57 metres, the Ebstorf mappa mundi is among only a handful of large-format medieval maps that have survived into the present.

In medieval times, maps of the world were created with the intention of ordering and arranging knowledge about the world in a manner consistent with biblical knowledge.

Sources from the Middle Ages

Curiosity and thirst for knowledge repeatedly generate new insights into a time long gone. But how do the researchers go about discovering answers to their questions? They hunt for clues in their “readings” of castles, earthenware vessels, and manuscripts. Disciplines such as archaeology, history and German language, literature and culture investigate historical sources and artefacts. Sometimes even tiny clues suffice to solve a puzzle, for example words in Old High German in medieval manuscripts. The researchers follow up on these clues meticulously and piece together knowledge concealed within them to fit the jigsaw together and reveal a complete picture.

“If we want to study German from its beginnings, we have to rely on what has come down to us in writing,” German Language, Literature and Culture scholar Professor Stefanie Stricker explains. Entries in manuscripts written in Old High German shed light on what caught the interest of people in the Middle Ages. Researchers are now tapping into modern resources such as digitised manuscripts to chart the sources situation and the culture of this period. Stefanie Stricker has particularly high praise for the extensive and detailed digitised material held at Bamberg State Library.

Historical Materials

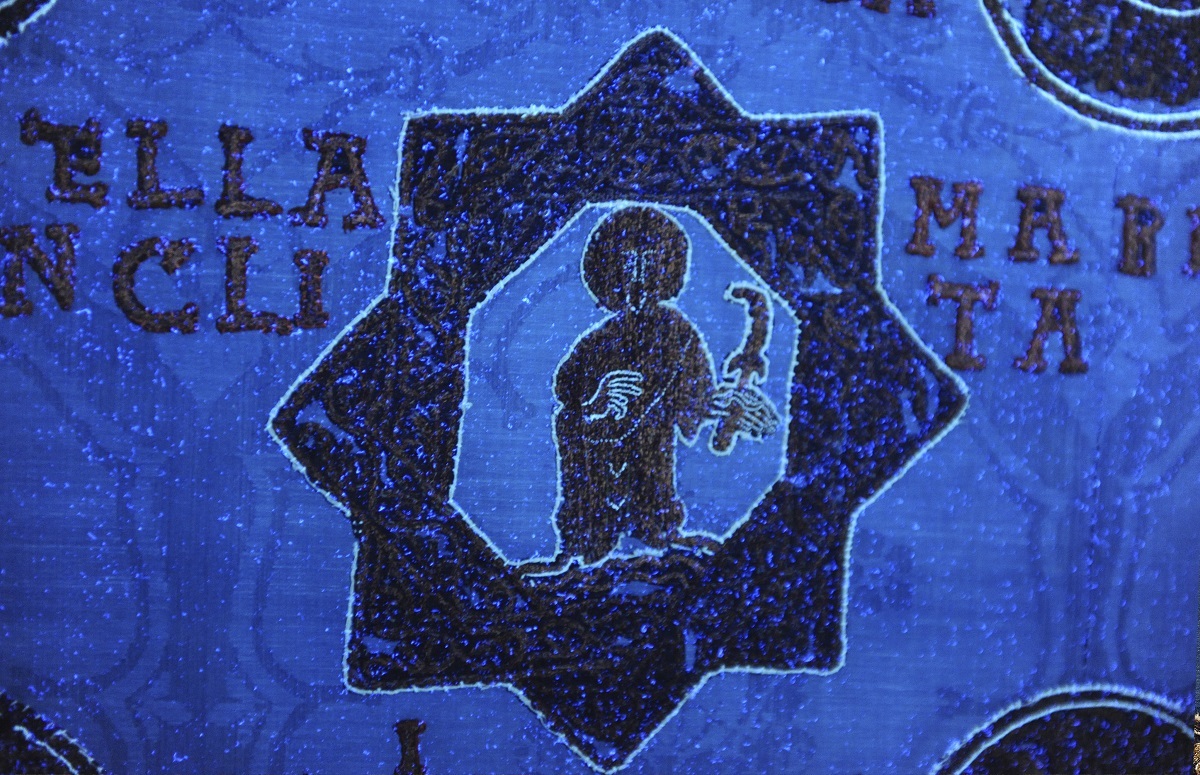

Experts can glean a wealth of information about the past from textiles, metal, wood and stone. Such materials can, for instance, indicate the period when an object was created. “At the University of Bamberg,” remarks art historian Professor Stephan Albrecht, “we combine the humanities with the natural sciences in a unique fashion.” He cites the research project he led on the imperial robes as an example.

These six splendid robes from the early eleventh century are believed to have belonged to Emperor Henry II and his consort Kunigunde: “The mantles are a sensation. They are the only precious textiles dating back so far that have survived in such an amazing state of preservation.”

Art history researcher Dr. Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai has analysed the medieval mantles from the perspectives of history and art history. Technological examinations of the garments were performed by textiles conservator Sibylle Ruß together with Anne Dauer. And analyses of the material were performed by biologist Ursula Drewello.

For art historian Tanja Kohwagner-Nikolai, the discovery of preliminary design marks on several garments was the most important finding from the research project: “The preliminary marks give us very good insights into the work process. We now know that there was a plan for the embroidery and that nothing was left to chance.” These findings enabled the researchers to refute earlier hypotheses and establish beyond doubt that errors in the embroidery process could be ruled out.

Insights into the study of the spectacular imperial mantles:

This multimedia feature presents the University of Bamberg’s “Medieval Culture and Society” research focus area.

Writing and editing: Patricia Achter

Video on the fascination of the Middle Ages: Christian Beyer; Music: Eberhard Kummer

Video on European identity: Johannes Titze, Benjamin Herges

Video on sources analysis: Benjamin Herges

Translation: Sarah Swift

Has your curiosity been piqued? You may wish to check out our multimedia features on other Bamberg research focus areas!

![[Translate to English:] Gabriele Knappe [Translate to English:] Gabriele Knappe](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/1/csm_Gabriele-Knappe_7672b1cbc4.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Ardistan Moschee [Translate to English:] Ardistan Moschee](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/3/csm_Ardistan_Moschee-Korn_79c0b02b13.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Lale Behzadi [Translate to English:] Lale Behzadi](/fileadmin/_processed_/b/5/csm_Behzadi_authorisiert_812d428282.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Laon Gerichtsportal [Translate to English:] Laon Gerichtsportal](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/1/csm_Laon_Gerichtsportal_a617f28358.jpg)